Research

What drives the development of an organism? How do individual cells coordinate to form tissues and organs? D'Arcy Thompson first questioned how forces shape tissues. Since then developmental biologists have emphasized how genetics control developmental biology. At this moment in history, we can investigate the physics of development - building on the wealth of genetic information and taking advantage of state-of-the-art microscopy and laser microsurgery. Development of living organisms requires coordination of cells. Viewed as a Collective Adaptive System, cells act as autonomous agents responding to stimuli from their neighbors and the environment to collectively produce an emergent behavior. We investigate the physical processes that coordinate these cells through the dynamic challenges of development.

Biomechanics of Drosophila Embryogenesis

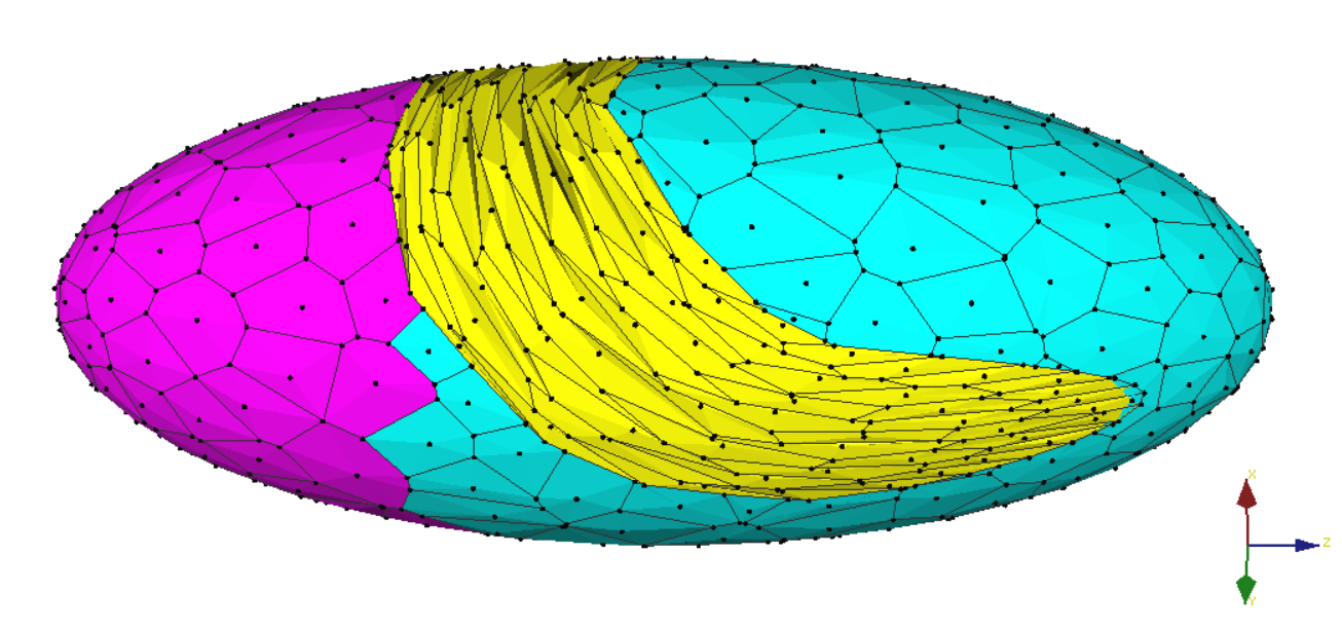

Midway through Drosophila embryogenesis, two epidermal tissues dramatically untagle in a process that requires cellular coordination spanning the entire embryo. This stage of development is called germband retraction. Using a novel surface-wrapped cellular finite element model, we have found that germband retraction is mechanically robust to cell-level tension. This finding suggests during retraction the embryo does not require careful regulation of force-producing genes. Instead, cells coordinate their directed migration through their shape. Highly elongated cells in one tissue, the amnioserosa, are sufficient for successful retraction even with abnormal tensions among the cells. Interestingly, these cells are elongated earlier in development – serving as a store of morphological information that coordinates the forces needed for retraction. In this case, and perhaps more generally, cellular force strengths are less important than the carefully established cell shapes that direct them.

See our article in Biophysical Journal

Calcium signaling in Drosophila Wound Healing

When the epidermis is injured, undamaged cells surrounding the wound must coordinate their healing effort. Cells can communicate via calcium signaling, which is actively channeled away from the wound. In the Drosophila pupal notum, we have found this signaling occurs in a series of waves expanding and flaring several cells away. This signal then coordinates cell migration to fill the wounded region.

I am modeling this process using a chemo-mechanical vertex model. Each cell in the model is represented as a 2D polygon with mechanically active components to allow migration. The mechanical forces are activated by chemical signaling among cells. Using this model, I hope to learn how cell communication coordinates cell migration.

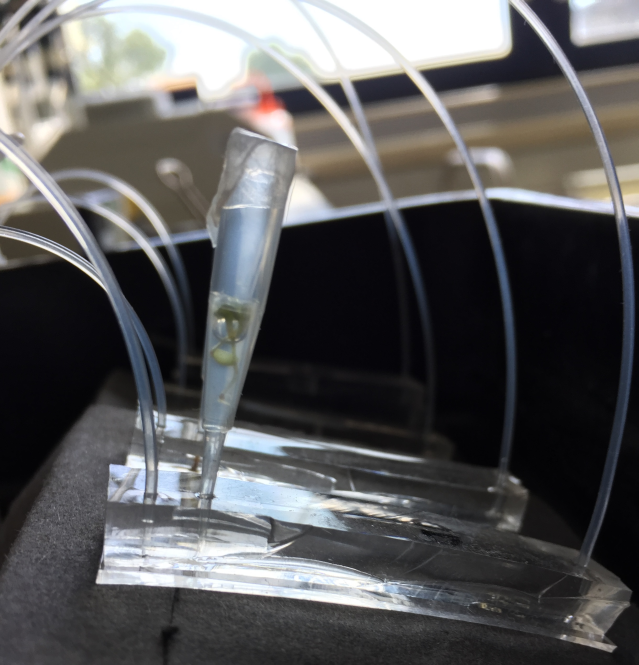

Experimental Microenvironment Testing Plant Root Branching in Complex Soil

In Arabidopsis, cells coordinate to pattern root architecture, strategically investing resources for growth to conserve energy while optimizing nutrient acquisition. Root cells communicate with neighbors through auxin hormone signaling, sharing information about the changing soil environment. Global root architecture is hypothesized to be the emergent behavior of locally coupled non-linear feedback systems between cells responding to hormone signaling. We are testing this hypothesis both computationally with a mathematical hormone flux model and experimental using a microenvironment device. The microenvironment analyzes hormone response to precision-controlled nutrient delivery in microfluidic devices.

Read my review in Current Opinion in Cell Biology

Please contact Dr. McCleery at the e-mail link below to learn more information.